Volunteer computers broaden climate model forecasts

March 31, 2012 — andyextance

Climate Researcher Dan Rowlands. Credit: Oxford University

Possible world temperatures in 2050 cover a wider range than previous official forecasts suggest, with the increase on the hotter side, scientists have said this week. That conclusion is based on a massive experiment, running 10,000 simulations using donated time on more than 30,000 computers through the climateprediction.net project. “The warming could be nearer to 3ºC rather than 2ºC higher than the average from 1961-1990 by 2050,” said Oxford University researcher Dan Rowlands.

Today, the most used predictions for future climate come from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The IPCC brought together models from around 20 of the best groups in the world doing research in this area in the Climate Model Intercomparison Project phase three, or CMIP3. But with such a small number of models, they couldn’t explore the range of future temperatures well.

“The IPCC knows this,” Rowlands told Simple Climate. “So, its uncertainty estimate is based on results from much simpler climate models. A lot of people have questioned whether they’re missing a lot of the key processes that might become important as the climate changes.”

But to predict what climate change will do to the world in detail, scientists need models like those used in CMIP3. “Say you’re looking at flooding in the UK in 2050, you need some meteorological drivers to put into your flood model from these large, complex, climate simulations,” Rowlands explained. “People in that field basically use the range from CMIP3, because that’s all that exists. We wanted to go out and challenge the uncertainty range of warming projected in CMIP3.”

Do try this at home

More detailed data on potential temperature ranges could help improve efforts to predict climate change impacts such as UK floods, like the one caused by torrential rainfall in South Yorkshire on the 25th June 2007, shown here. Credit: Wendy North/Flickr

Understanding the range of temperatures output by modelling forecasts is just the kind of problem the computing power available to the climateprediction.net project is suited to answer. But climate models can have more than a million lines of software code, normally designed to run on high-power supercomputers. “Taking a climate model designed to run on a supercomputer and getting it to run on a home computer involves quite a lot of computing expertise,” Rowlands said. “To convert just one took the equivalent of one person doing it for a couple of years.”

So the team stuck to just that one model, creating 10,000 simulations from it by changing quantities related to the most basic climate processes, which Rowlands compares to tuning knobs. “There are a lot of tuning knobs that we don’t quite know the values of, because we just don’t have enough physical understanding or observational evidence,” he said. “A very uncertain value is for example, the rate at which ice falls through clouds or the rate at which heat penetrates into the deep ocean.”

The scientists checked the results the 10,000 simulations produced against patterns in the world’s surface temperature from 1961-2010, and threw out those that didn’t match up. They were left with around 400 versions of the model that they assessed had produced a plausible simulation of the changes. Using these, they then predicted what the Earth’s surface temperature would do for the period through to 2080.

Seeking certain properties

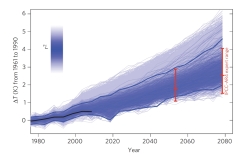

Ranges of average world temperature projections in Rowland's team's research. Blue colouring indicates how well models fit observations, with dark blue fitting best. The black line is measured temperature, and thick blue lines the ‘likely’ range of models. Red bars show the IPCC expert ‘likely’ range around in 2050 and 2080. All temperatures are relative to the corresponding 1961–1990 average. Credit: Nature Geoscience

Writing in a paper in research journal Nature Geoscience last Sunday, Rowlands and his colleagues say that their results show that forecasts in the range of 1.4-3ºC in 2050 are all equally believable. “We can produce model versions that warm up by almost a degree centigrade more by 2050 than anything else in CMIP3,” the scientist said. “These simulations look as plausible as any of those models. We would argue that this provides a useful set of additional scenarios that those in the climate impact and adaptation community could use.”

As well as providing data that other researchers can use to predict what a warming world might do to impacts like flooding, these findings could also show which tuning knob values we need to know more about. “It provides a good framework for being able to identify which processes give rise to uncertainty,” Rowlands said. “This could then hopefully inspire future research into either gaining more physical understanding or better observations that might help us pin them down.”

But another important thing that this research shows is the role the public can play in climate science by sharing their computers. “I think this shows how the public can contribute towards academic research that does get published,” Rowlands said. “Our group, and the research we put out, wouldn’t exist without the people who sign up to our project and contribute their computer resources to running models. We are very indebted to our participants for donating their time.”

-

In case you missed the links in the text above – you can sign up for climateprediction.net here.