Climate benefit from trees depends on location

November 19, 2011 — andyextance

By comparing forest temperature measurements from Fluxnet towers, like this one in Tonzi Ranch, California (not actually used in this study), with nearby weather stations in grassy fields, Xuhei Lee and his colleagues could determine the warming or cooling effect of forests. Credit: Dennis Baldocchi

Trees growing near the equator can directly cool local temperatures, while those nearer the poles can have a direct warming effect. That’s according to a team of 21 scientists from Germany, Canada and the US who have compared temperatures in North American forests with those in nearby open areas. Snow covered open land reflects sunlight back into space in the day, and cools further at night. Trees in such environments, meanwhile, absorb light in daytime and help trap heat near the ground at night. By contrast, in warmer areas, trees’ large, rough, surface area releases heat into the atmosphere more efficiently than open land. This direct effect operates separately to the role trees play in climate by absorbing CO2, but does contribute to their overall influence on world temperatures.

“It reinforces the notion that the benefit of tree planting depends on where you do it,” lead scientist Xuhui Lee from Yale University told Simple Climate. “Our data suggest that planting is beneficial south of 35 degrees north [the distance between the North Pole and North Africa, North Carolina or Tibet] and may be counterproductive north of that.” Another implication comes because weather stations are supposed to be located away from objects like buildings and trees that absorb and release heat. Consequently, the same effect could also influence global temperature records that we rely on to monitor climate change like the one produced by NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies. Lee said that though this might affect some local measurements, the overall historical records should be correct. He is more worried by what locating weather stations only outside forests does to the measured difference between the daily maximum and minimum temperature, known as the diurnal temperature range or DTR. “Our results show that DTR could be off by as much as 8ºC in some locations,” Lee said.

Staying cool

The locations of the pairs of forest and weather station sites Lee and his colleagues used for their analysis. Credit: Nature

Lee was inspired to investigate trees in the US and Canada by results from a forest in Israel close to a desert that could cool itself enough to survive, while being baked by the bright sun. “I was intrigued by a study by my colleague Dan Yakir published last year,” he explained. “In that, his team showed that a plantation forest in Israel absorbs more solar radiation than the surrounding open landscape and yet is cooler because trees are more efficient at dissipating heat. I wanted to check if this pattern also holds elsewhere.”

To do this, Lee and his colleagues turned to the “Fluxnet” network of meteorological towers. Located in forests to monitor flows of CO2, water vapour and energy, they have already been recording temperature and solar radiation for at least three years. They then compared measurements from each tower with figures from the nearest surface weather station operated by the US National Weather Service and Environment Canada. These stations are carefully placed in open grassy fields, so the comparison is effectively between measurements in side-by-side forested and unforested areas.

Writing in top science journal Nature this week, they found that forested land with a latitude greater than 45 degrees north – further north than Oregon, southern France and Northern Japan – was warmer than nearby open land. South of 45 degrees, maximum daytime temperatures in forested lands were lower than over nearby open land, but forest nighttime minimum temperatures were still higher. South of 35 degrees, forests were cooler than open land day and night. While the temperature data were clear, Lee said that developing a theory that explained how trees’ influence changed with location was the greatest challenge in this work.

A warming paradox

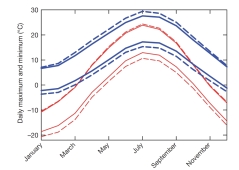

Average daily maximum and minimum temperatures for the forests (solid lines) and the surface stations (dotted lines) from 28–45 degrees North (blue lines) and 45–56 degrees North (red lines). Credit: Nature

Lee and his colleagues haven’t yet addressed how these effects balance against trees’ role in controlling temperatures by removing the heat-trapping greenhouse gas CO2 from the atmosphere. However, Dan Yakir’s research in 2010 studying the Yatir Forest in Israel sought to answer that question. In his study the trees absorbed the sun’s energy, therefore trapping heat in the atmosphere, while the surrounding desert reflected heat back out into space. Yakir calculated it could take up to 80 years for the trees to take up enough CO2 to balance out atmospheric heating from the extra energy they absorb directly. By contrast, they found desert replacing vegetation over the past 35 years has effectively slowed down global warming. The sunlight the desert reflected was equivalent to around 20 per cent of the expected warming effect from the CO2 rise over the same period. However Lee calls this result “paradoxical” as, at a latitude below 35 degrees north, the forest itself is much cooler than the surrounding desert while supposedly warming the Earth overall. He therefore questions whether it’s accurate to combine CO2′s warming effect with energy absorption and reflection on the Earth’s surface in this way.

Lee and his colleagues now hope to follow up this work by collecting more data in southern latitudes. However, the researchers note that their findings should make other scientists look again at their ideas on forest planting and weather station positioning. Also, as 30 per cent of the surface of Earth’s land is covered with trees, the behaviour Lee’s team observe could also affect climate predictions. “Forests are complicated ecosystems with subtle climate system effects,” said Lee’s co-author, David Hollinger, a scientist with the US Department of Agriculture Forest Service. “This study underscores the need to retune climate models to reflect that complexity so we can get a better picture of the role forests play in the landscape.”

Comments (0)

You don't have permission to comment on this page.