2020 target offers climate change control hope

October 29, 2011 — andyextance

Scenarios in which CO2 emissions can be controlled and keep global average temperatures less than 2°C above the average before the world became industrialized are technically feasible, according to Joeri Rogelj from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. Credit: IceCatSeoul/flickr

To avoid the most serious consequences of climate change, the amount of CO2 humans produce must peak and then start to decline within this decade. And, according to Joeri Rogelj from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, it is possible to do this. Rogelj and his colleagues analysed 193 different climate change scenarios to determine whether global temperature would stay less than 2°C above the average before the world became industrialized. They found that, as long as the annual amount of greenhouse gases humans emit is less than the equivalent of 48 billion tonnes of CO2 by 2020, there is a “likely” chance. “Technologically and economically feasible paths exist to limit emissions and the global temperature increase in the long term,” he told Simple Climate. “When we go outside this range, we cannot be sure this still will be possible any more.”

After the Copenhagen Climate Change Conference in 2009, Rogelj was part of one team among many who tried to work out the likely consequences of the Copenhagen Accord climate deal signed there. Though they came up with similar messages, there were also potentially confusing differences. Consequently, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) published an Emissions Gap Report in December 2010 trying to bring together pathways that might keep warming below the 2°C level that it’s considered it would be dangerous to exceed. On Sunday, writing in research journal Nature Climate Change, Rogelj and colleagues from seven other countries extended the UNEP report’s scientific framework for comparison to an even broader set of research. “With this study we can give robust findings of what a large body of scientific scenario literature tells us about future emissions paths,” he said. “We provide a snapshot of the current knowledge across economic and climate modelling.”

Likely chance

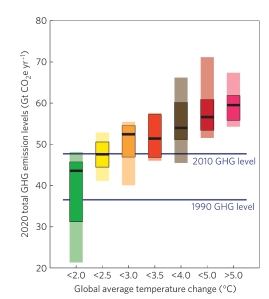

The range of global total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2020 from the models collected by Rogelj and his colleagues, sorted by the different temperature limits they reach during the 21st century. Shaded areas represent the minimum–maximum ranges; the coloured bounded rectangles the more common ranges seen in models (15-85% quantiles), and the thick black horizontal lines the median average values for each temperature level, respectively. Horizontal blue lines represent median average 1990 and 2010 emissions. Greenhouse gas emissions are measures in the equivalent of billions of tonnes of CO2 emitted per year (GtCO2e yr-1) Credit: Nature Climate Change

The 193 scenarios all represent possible directions that the world could evolve in this century, and the greenhouse gas emissions that would be associated with them. “These scenarios take into account how technologies can scale up, how infrastructure can be replaced over time, economic constraints and available resources, amongst other things,” Rogelj said. “All the scenarios represent technologically and economically feasible futures. We found that scenarios that have a likely chance – greater than 66 per cent probability – of limiting global temperature increase to below 2°C have emissions in 2020 equivalent to 31 to 46 billion tonnes of CO2.” By comparison, they estimated that greenhouse gas emissions in 2010 totaled the equivalent of 48 billions tonnes of CO2. Emissions must therefore peak and fall back below the 2010 level within a decade.

The authors of the Nature Climate Change paper warned that many of these scenarios rely on energy generation that goes beyond “carbon neutral” and actually absorbs CO2. This may be possible with biofuels or carbon capture and storage, but it hasn’t yet been demonstrated on a significant scale. Rogelj also said that most of the scenarios are looking for lowest-cost solutions, but that it may still be possible to meet the 2°C target at even higher emission levels. “We cannot say that it will be impossible to stay below 2°C,” he said. “However, we can say that it will most likely be more difficult and more expensive to reduce emissions in the long term. That therefore would involve higher risks.” Rogelj now hopes to go on and study what happens if emissions do exceed the thresholds this work suggests, and what what could still be done to control warming if they do.

Peered over

Most scenarios in which the world warms by less than 2°C require the energy sector to capture CO2, using technology like this post-combustion CO2 capture pilot plant at Huaneng Beijing Co-Generation Power Plant. Credit: China Huaneng Group

Yet, despite these concerns, Rogelj asserted that he and his colleagues are confident in the quality of the models they brought together. That’s because they were careful only to include studies that had been through the process of scrutiny prior to publication known as “peer review”. “We incorporated data and models which were already scientifically reviewed and from which the validity for our question was demonstrated in the peer-reviewed literature,” he explained. “By making sure to only use results published in the peer-reviewed literature, we make sure we can have confidence that there is at least a basic level of quality.”

In turn, putting their “snapshot” through the same process ensures it can influence future debates on climate. “The fact that this study is formally peer-reviewed and therefore can be included in assessments like the next report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is an important reason why publishing such methodologies and results is critical for science,” Rogelj said. “We can now communicate robust findings from a large range of studies to a wider public.”