Atlantic cold tongue tells of humans’ climate impact

February 12, 2011 — andyextance

Wind waves depend on wind speed and have long been logged by ship crews. Ocean wind data corrected with wind-wave heights suggests a slow down of the southeast trade winds in the equatorial Atlantic. Credit: Image courtesy of Ship DAVID STARR JORDAN, NOAA Photo Library.

Humanity has significantly altered the climate in the tropical Atlantic between 1950 and 2009, gradually weakening the area’s trade winds, University of Hawaii at Manoa researchers say. That effect is caused by burning fossil fuels, Hiroki Tokinaga and Shang-Ping Xie explain. However, it is more directly driven by the aerosols of soot and sulfur-based particles this releases than global warming caused by the resulting CO2 greenhouse gas emissions.

Falls in aerosol emissions now look set to reverse this trend, Tokinaga notes, showing how government actions can influence the environment. “Human-produced aerosol emissions had continuously increased until the 1970s, but then they started to decrease because of legislation in North America and Europe,” he told Simple Climate. “Increased greenhouse gas forcing contributes to a broader warming of the tropical Atlantic. Another climate shift might happen when the increased greenhouse gas forcing gets stronger than the aerosol forcing in the next few decades.”

Writing in a Nature Geoscience paper published last Sunday, Tokinaga and Xie analysed data collected directly by ships over the past 60 years. Taken at face value, these appear to show that wind speeds have increased, but Tokinaga explains that this is due to the evolution of ship design. “As ships get bigger the heights of their anemometers, the instruments measuring wind speed, have also increased,” he says. “Because wind speed tends to get stronger with height, raw wind speeds have artificially increased.” Previous attempts to resolve this issue tried to use information about ship height, Tokinaga adds, but those measurements are only available in about half the historical records. Instead Tokinaga and Xie use wind-wave heights, which depend on and are collected alongside wind speeds, to gain accurate information from over 5,000,000 ship reports.

The Atlantic cold tongue speaks

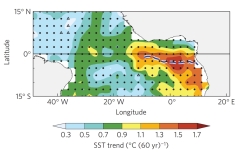

Changes in June-August sea surface temperature change from 1950-2009 based on measurements taken from ships in the equatorial Atlantic. Red indicates the greatest increases and light blue the greatest decreases. Africa is on the right of the map, and South America on the left. Credit: Nature Geoscience/Hiroki Tokinaga

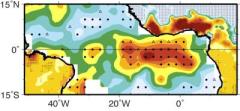

The results showed a number of noticeable changes since 1950. “The southeasterly trade winds have weakened, ocean temperature patterns have shifted over the eastern equatorial Atlantic, and Guinea coast and equatorial Amazon rainfall has increased during the last 60 years,” Tokinaga summarises. While sea temperatures generally rose across the region over this period, the Atlantic cold tongue, a projection of colder water that stretches out from the eastern tropical Atlantic, suffered the greatest increase of 1.5ºC for the June-August period. Southeasterly trade winds shape the Atlantic cold tongue by enhancing upwelling of cold water during summer in the Northern Hemisphere. Weaker winds mean less cold water wells up, resulting in the more rapid increase in sea surface temperatures.

Tokinaga and Xie explain that these changes can be linked to fossil fuel burning because most of that burning happens in the northern half of the planet. This has been shown to have resulted in less warming in the Northern than Southern Hemisphere during the 20th century. “Aerosols have a cooling effect by reducing solar radiation reaching Earth’s surface,” Tokinaga explains. While the CO2 burning fossil fuels emits has a worldwide warming effect, the cooling effect of aerosol emissions are concentrated in the north. Temperature differences play a key role in determining wind speed, and Tokinaga says the varying trends on either side of the equator are behind the weakening winds. “This change in the north-south thermal contrast is most likely to relax the trade winds over the tropical Atlantic,” he points out.

Changes over the last 60 years in the August marine cloudiness and land rainfall over the tropical Atlantic. Yellow to dark red indicates more cloudiness/rainfall; light blue to gray, less cloudiness/rainfall. Over land, dark red = 40 mm/month more rain, and grey = 40 mm/month less rain. Note the significant increase in rainfall on the Guinea coast, in Africa, on the right. Credit: Hiroki Tokinaga, IPRC/SOEST/UHM

The slowing Atlantic trade winds have not been spotted before because their long-term changes are still smaller than seasonal and year-to-year variations, but they are nonetheless important, Tokinaga says. “The weakening of trade winds might cause a reduction in oceanic nutrients and thus fewer fish through suppressed ocean upwelling,” he suggests. “The ocean warming pattern also implies sea-level rise in the eastern equatorial Atlantic. These changes matter to people who live in the surrounding regions.”

Trade winds look likely to strengthen again due to the combined impact of emissions controls and ongoing warming, which could pose further problems. “The resulting increase in climate extremes would add burdens to an ecosystem and to a society already stressed by global warming,” warns Tokinaga.

Comments (0)

You don't have permission to comment on this page.